This is the third part of the series, in which our Research Fellow Matthias analyses thousands of recordings from the UK singles charts using audio signal processing techniques. You can read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

How does music change over time? Does it get faster, more complex, more diverse? In the course of the last few weeks we have learned that many aspects of music don't seem to follow that kind of simple trend. Rather, changes happen in less predictable ways. One of the most surprising examples of that emerged when we looked at the development of rhythm regularity in the UK charts...

The 80s Regularity Hump

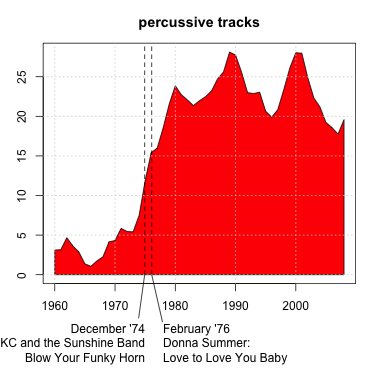

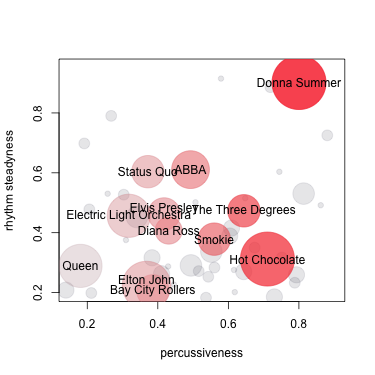

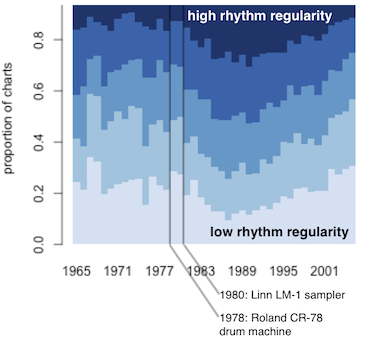

The figure below visualises data that we've already used in the first part of this series to look for disco songs: rhythmic steadiness, or "rhythm regularity", as we will call it in here. To measure rhythm regularity we have written some audio analysis code that outputs a high value if the rhythm in an MP3 file often changes between consecutive 16 second sections, and a low value if consecutive sections don't change much. Our regularity extractor is based on a mathematical description of the rhythm in every second of a track known as Fluctuation Patterns (see Further Reading, below). When we plotted rhythm regularity over the years, to our surprise we didn't find a simple trend in either direction...

Instead, we found a regularity hump, right at the beginning of the 80s: the dark blue area shows the proportion of the charts in every year that is taken up by the most rhythmically regular tracks. Around the start of the 80s, the proportion of the most regular tracks increases noticeably, while the proportion of the most irregular ones diminishes. What could have fuelled this trend? One obvious suspect is the introduction of new technology. We have marked the release date of the first widely used drum machine, the Roland CR-78 in '78, and the first influential digital sampler, the Linn LM-1 in 1980 in the figure. We can't prove the connection but it's certainly a striking coincidence. Why does the proportion of highly regular tracks wane again in the mid 90s? Maybe people were fed up with very rhythmically regular music, or maybe drum machines simply got better at producing more diverse rhythms.

In either case, if this hump is really related to drum machines and samplers, we'd expect to see the trend in other kinds of data as well.

The 120 bpm Tempo Crunch

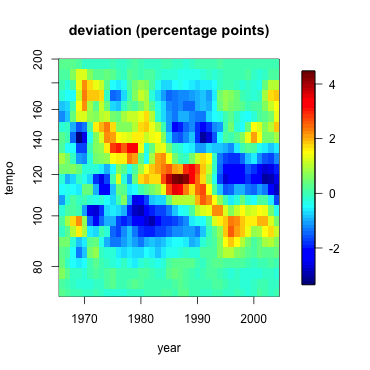

As the 80s seems to have been an unusual time for rhythm, it would be no surprise if we also saw striking things in the tempo of 80s music. We ran our tempo tracking software on the whole charts collection to measure the tempo of each section of each track in beats per minute (bpm). We then picked a single bpm value for each song by choosing the one attached to the most seconds of audio. At a first glance a plot of the average tempo per year didn't look very interesting (you can see it here). But then we noticed something unexpected. Have a look at the image below.

The heat map above shows you which tempos (in bpm) were unexpectedly popular in which years. For example, see the dark orange dot around tempo 100 in 1969? That means that tempos around 100bpm were more popular than usual that year (up by more than 2 percentage points). Admittedly, what's more striking is that there seems to be a downward pattern, as if some kind of music was getting slower and slower over the years. There's also a a strange cluster of tracks around 120 bpm from the early 80s to the early 90s - the big red blob in the middle.

Some tracks from the red blob:

Prince - 1999 (120 bpm)

Frankie Goes To Hollywood - Relax (117 bpm)

808 State - In Yer Face (120 bpm)

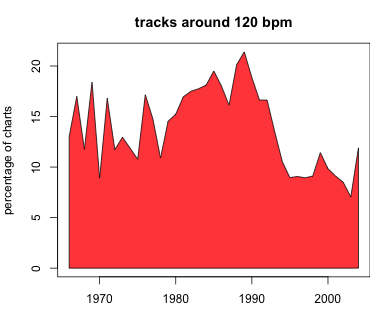

Before we ask what this cluster means, let's make sure that this trend is really there, i.e. that the proportion of tracks around 120 bpm is really higher from 1982 to 1991 than in the rest of the time. It may seem obvious from the figure below, which plots the proportion of tracks between 116 and 124bpm over time. To be really confident that this is not due to chance we use a statistical test, a "2-sample test", which can check whether the difference is significant... and it is, with 95% confidence we can say that the difference is between 5.5 and 8.1 percentage points (details).

Our first thought was that songwriters in the 80s must have turned on their drum machines, loved what they heard and wrote a song to that beat - without changing the default tempo setting of 120 bpm. I would love this to be correct, but I have a hunch that it's not, especially after having found this highly interesting manual for writing a hit single written by The KLF in 1988. They say that "the different styles in modern club records are usually clustered around certain BPM’s: 120 is the classic BPM for House music and its various variants, although it is beginning to creep up", and also, "no song with a BPM over 135 will ever have a chance of getting to Number One" because "the vast majority of regular club goers will not be able to dance to it and still look cool".

In this track the KLF follow their own advice.

The KLF - 3 a.m. eternal (120 bpm)

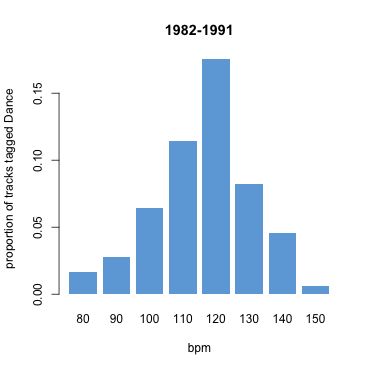

It seems that the KLF have a point. We wanted to know, and compared the tempo estimates to our Last.fm tags, especially the "Dance" tag. The figure below suggests that the KLF were really right. We took all tracks within ranges of 10 bpm (75-85, 85-95, ... , 145-155) and plotted the proportion of them that were tagged "Dance". It turns out that the KLF had quite a good grasp of what was true from 1982 to 1991. The proportion of tracks tagged as Dance is clearly highest around 120 bpm...

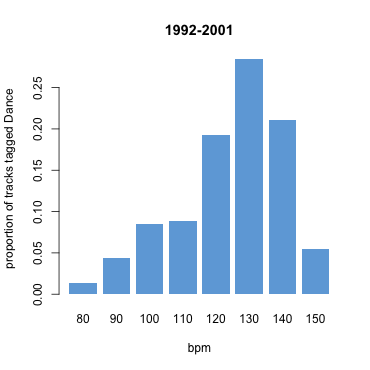

So was the drum machine a curse? It's been a blessing for many dancers, and it has undeniably led to the emergence of whole new genres of music, often dance music. And dancers have taken it from the club to the charts. Incidentally, somewhere along the way they must have learned to look cool even at higher bpm rates... what we see for the years 1992 to 2001 suggests a rather radical change to quicker dance music quite different from the KLF's suggestion that the tempo is "creeping up". Check the figure below.

Dance music in the 90s has clearly moved on, even the songs that did get into the charts, and its got faster. However, there seems to be another current of music that counter-balances this, as our tempo heatmap further up suggests (though it doesn't prove it).

As a reward for trying to understand all our data visualisations today we leave you with two of our new multi-tag radio stations.

Next week, bring some some earplugs, as we will try to find out where all the racket comes from in The White Noise Boys [Edit: title changed to Survival of the Flattest].

Anatomy of the UK Charts series so far

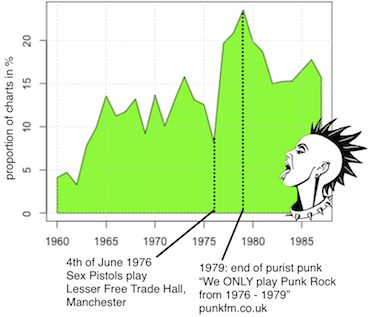

Percussiveness and the Disco Diva - on the rise of disco in the mid 70s

Clash of Attitudes - on automatically telling punk from art rock

The Curse of the Drum Machine - this post

Further Reading

The original article on the Fluctuation Patterns feature is by Elias Pampalk, Simon Dixon, and Gerhard Widmer: On the evaluation of perceptual similarity measures for music. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx-03), pages 7–12, 2003.

If you want to detect the tempo of a track automatically, try Matthew Davies's tempo tracker in the Queen Mary Vamp plugin library or Simon Dixon's BeatRoot.