In a recent interview with the Guardian the young British pianist Benjamin Grosvenor voiced his frustration about his brother’s taste in music: “Those modulations at the end of the songs! They've sung it all already, and then to create a greater emotional effect, they put it up a tone.”

By “they” he’s referring to his brother’s favourite band, Westlife, and the modulations he describes are an old trick you can find in many a songwriters’ toolbox: the gear shift!

Hall of Shame

So is Grosvenor an intellectual snob, an arrogant piano kid? Well, he seems to be quite a nice guy, and he certainly isn’t alone in his disdain of gear shifts. There’s even a website which features a Hall of Shame of supposedly abhorrent examples of this phenomenon, eight of which are by Westlife. The book author Wayne Chase, too, dedicates a section of his songwriting manual How Music Really Works to what he calls “Shift Modulation”, and the section’s heading warns the eager reader in large letters: “Don’t Do This!”.

So let’s have a look at the symptoms. The video below demonstrates the 1-semitone gearshift in Westlife's song “I'm Already There”, see if you notice when it happens.

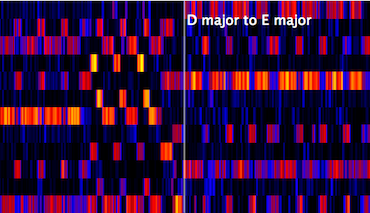

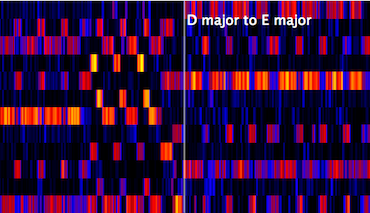

The chroma visualisation at the bottom of the video shows you which notes (from A to G#) are present in the piece at a certain time. You can easily spot the point where all notes move one semitone up, can you also hear it? The video also suggests that there may in fact be a few good reasons why some musicians should find gear shifts hard to bear.

Firstly, gear shifts are easy to compose. If you have a song in the key of Eb major (as in the above example), then all you need to do is play/sing everything one semitone higher from a certain point; in this video, the song shifts from Eb major to E major, and that’s pretty much it. This makes gear shifts a relatively superficial means of creating complexity in a song, much easier to accomplish than, say, a whole new part of a song, or indeed a more complicated key shift. The reasoning is then: if you need such a simple means of making the song more interesting, it can’t have been interesting in the first place.

Secondly, gear shifts actually sound very cheesy. They have a predictably uplifting feel, so they tend to be used in sentimental songs such as “I’m Already There”, or crowd-pleasers like Bon Jovi’s “Living On A Prayer” (check the gear change at 3:24 in this video).

And there’s a third reason, which we will find out about soon with the help of our music processing methods.

Gear Shift Police

Since the last blog post, we’ve filled a few holes in our collection of UK charts recordings, and I have looked a bit more into harmonic descriptors of audio. One of the outcomes is a gear shift detector.

Like our measure of harmonic complexity in an earlier blog post, the gear shift detector is based on the chroma feature that you saw in the video above. By matching the chroma feature of a song section to profiles of musical keys it is possible to estimate which key fits best. The gear shift detector makes use of this technique: it goes through all song positions and matches two kinds of key profile pairs to the data: those that model a gear shift (the key after the song position is one or two semitones higher) and those that don’t (the key stays the same). If the best gear shift model fits better than the respective model without a key change, we have good evidence for a gear shift.

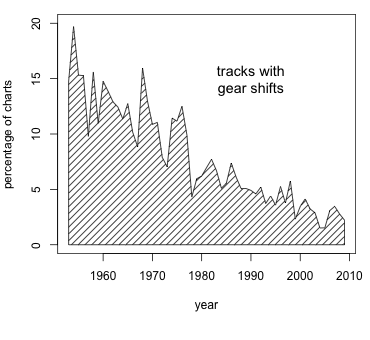

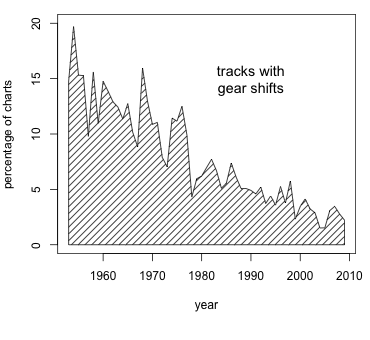

In addition, to filter out tracks which fit both models badly, we use a feature which is sensitive to any large scale modulation, but will remain low if there is no such large scale modulation. We ran the gear shift detector on the whole charts database, and found a strong trend that would please our gear shift haters!

The proportion of songs with gear shifts is substantially declining over the history of the charts, from a staggering 15% in and around 1960 to consistently lower than 4% in the first decade of the current century.

The high frequency of gear-changing songs before 1970 is our best guess for the third reason musicians dislike them: there are just too many of them. Perhaps gear shifts were overused? For the moment it’s mere speculation to attribute the decline of the ratio of gearshifting songs itself to their high frequency in the early days of the charts, but it is quite easy to imagine that they just ceased to be special (if they ever were).

Merry Gear Shift Everyone

I wonder at which point the gear shift turned from a relative novelty to an established songwriting tool, rendering anyone who uses it less ‘cool’? Even The Rolling Stones, definitely one of the coolest bands of their time, could get away with 'shifty' songs, as can be heard in this excerpt:

Rolling Stones - Come On

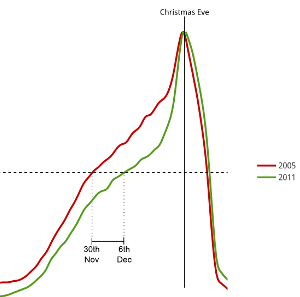

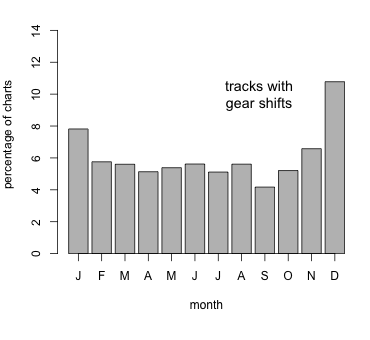

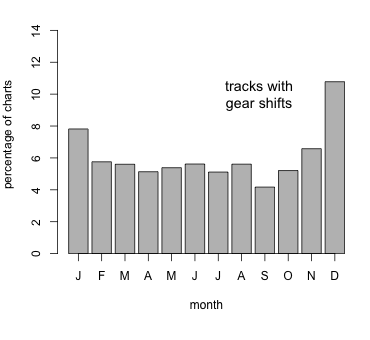

However, later on, gear shifts seem to have become irreconcilable with artists who consider themselves to be cool. For example, our detector does not find a single U2 hit with a gear shift. And it’s conceivable that consumers, too, started considering themselves as cool and to shun gear shifts. However, there is a time of year where songwriters seem to catch music buyers off guard — at Christmas, as the figure below impressively illustrates.

The graph shows the percentage of gear-shift songs in the months they hit their highest position. It is substantially higher in December than in all other months, and more than twice as high than in September. It doesn’t come as a surprise, then, that considering only tracks that feature the word “Christmas” in their title even has a gear shift ratio of 31%.

I’m Going To Make A Change For Once In My Song

I personally think we shouldn’t be so harsh as to condemn all gear shifts in the charts (though if you’re interested in doing so here’s the list) — there are some true gems.

Some of you might have recognised the section heading as a (slightly punned-up) line from the song “Man In The Mirror”, famously performed by Michael Jackson. While Jackson was never in danger of out-gearshifting Westlife, he certainly came up with some juicy specimens. “Man In The Mirror” does in fact contain one, nicely placed on the lyric “change!” (see video, gear change at 2:52), but really that’s just a warm-up exercise. Other examples include

“Rock With You” (video, 2:31),

“Earth Song” (video, 3:46), and the more recent “Cry” (video, 3:11).

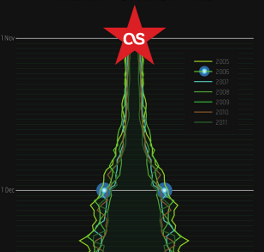

During the last decades of his career there was also a tendency to increase the number of gear shifts per song. The songs “You Are Not Alone” (video, 3:31, 4:10) and “Heal The World” (video, 4:33, 4:58) include two each, and “Will You Be There” takes the prize with three (video, 2:06, 2:30, 2:53), making the King of Pop the true King of Gear Shifts. The figure below shows the chroma representation of the first gear shift in Will You Be There, click to see a longer excerpt.

And why not? To be sure, a song has to offer a lot of other goodness to justify gear shifts, but maybe I could even convince Benjamin Grosvenor that without them pop music would be poorer. I quite like the effect it produces, and as long as you don’t overdose...

But tell us what you think! Would you like to be able to exclude gear shift songs from your Last.fm radio? Or even seek them out?

]]>